| Read Log, May-June 2021 | |||

| By Tal Cohen | Sunday, 15 August 2021 | ||

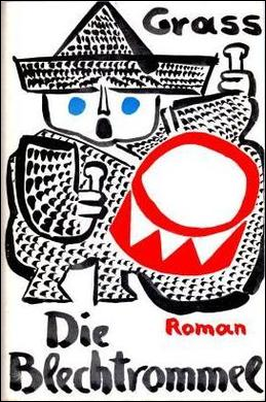

Jude the Obscure by Thomas Hardy. The bildungsroman that lets the proletarian dream of advancement dies, while also attacking the Church and the institution of marriage. That’s remarkable and ground-breaking for its time, but... if only the prose wasn’t so annoying. Characters that endlessly quote scripture, poets, and obscure authors, crude symbolism (e.g., around Jude’s treatment of animals), and more, just make the book a tiring read.   Killing two men, each of which is potentially your father, is a pretty serious Oedipus complex; doing it by forcing one to face the Nazis as a resistance fighter, and later forcing the other to face the Soviet victors as a Nazi, takes the irony to a whole new level. And of course, it all drips with symbolism. (The drum itself, as described numerous times in the text and as drawn on the original German cover, is painted red and white. Yet the Hebrew publisher chose to keep the same image, while changing the drum’s colors to red and blue. This is beyond my comprehension.)   It’s a great interview, one of the very few Watterson ever gave; and the selection of strips to accompany it is well chosen. One thing that did bother me, though, was Watterson’s take on webcomics, which I found to be condescending. He doesn’t understand how they can get an audience, and how can they make a living. What he ignores is how amazingly small was the number of artists who, like himself, made a living off of comic strips (not comic books, mind you), compared with the surprisingly large number of people who make a living through writing webcomics, or just enjoy a large audience without making it their main source of income. Of course, in many cases, even those that make a living from their comics don’t always make the most from the comic strip itself, but rather from books, merchandising, kickstarter campaigns for wacky stuff, and giving talks, for example. Watterson had the huge privilege of being able to fend off merchandising his creations; others don’t necessarily view that as evil. Plus, modern comic strip writers are able to address niche audiences — such as grad students, in the case of PHD Comics. They can try (and thrive!) with new formats that would never have succeeded in the past — for example, Dinosaur Comics takes the principles of OuBaPo, which Watterson admits in the interview to have never heard of, to a level of popularity few imagined possible. And they sometimes make use of the digital medium in a way that, naturally, is impossible in print, such as the seemingly endless zoom levels of the xkcd strip “Pixels”. Apparently, audiences and creators alike benefit from this new world, where syndicates are no longer required for an independent creator to succeed.

| |||