| Read Log, April-May 2019 | |||

| By Tal Cohen | Saturday, 08 June 2019 | ||

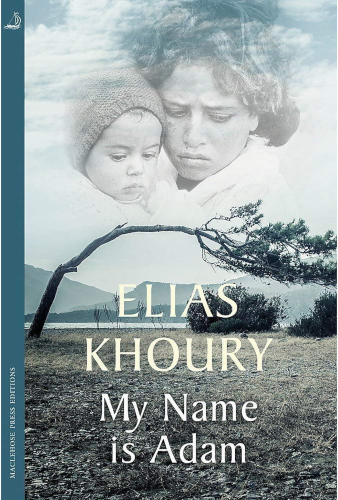

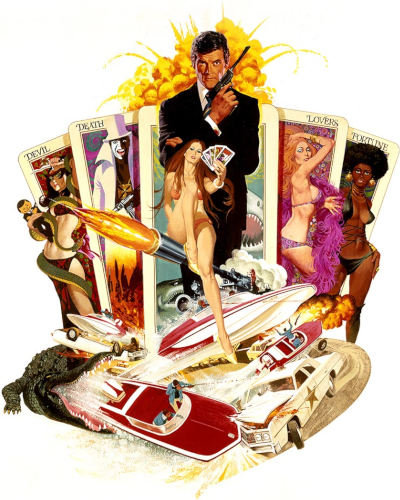

On the Poetry of Yonatan Ratosh by Dan Miron. This is a chapter from Miron’s book Four Facets in Modern Hebrew Literature, published as a stand-alone volume. The analysis is absolutely brilliant, and sheds a beautiful light on Ratosh’s poetry, pointing at its Hemingway-like qualities.   The plot begins as a rather stupid story — a soviet agent lost the money given to him for the job, and was now trying to recover it in the casino (the only way to earn it back quickly enough). The secret service decides to send Bond to beat him in the casino, thereby making the French communists aware of that person’s betrayal and causing damage to his organization. Absolutely stupid. As it progresses, however, the story greatly improves, and the end is rather surprising. The book has an almost le Carré-like approach to the business of spying, very much unlike the Bond movies (or, I presume, the following Bond novels).   The first part of the story resolves around Waddah al-Yaman (وضّاح اليمن), which turns out to be a known story (and a nice one, too) rather than something Khoury made up. However, the way Khoury (“Adam”) unfolds the story oscillates between fascinating and annoying. There isn’t a single page that doesn’t cite a random poet or scholar, in what seems like endless name-dropping. This style is maintained throughout, to a lesser yet still disturbing level. “I will not use the words of Albert Camus,” writes Adam, and proceeds to use the words of Albert Camus. Endless citations (in a novel, mind you) to well-known as well as obscure Arab poets, but also to Shakespeare, Gogol, Borges, ... Adam notes “I do not wish to be a symbol,” but the book is overloaded with symbolism. That, by itself, is not a bad thing, but it’s done with little or no subtlety. The analogy between Muphid Shchada, the boy who was killed on the ghetto fence, and Christ, is alluded to again and again. The eyes and blindness motif, the noise and silence motif, the smell motif — these are all just too blunt, pushed in the reader’s face again and again. But these are all nits. The book, overall, is a very good one, both for its literary value and, far more so, for the importance of the history it presents, particularly to Hebrew readers. Too sad that so few of us will read it.  Fleming really enjoys mocking the Americans: “He was reminded to ask for the ’check’ rather the ’bill’, to say ’cab’ instead of ’taxi’ and (this from Leiter) to avoid words of more than two syllables. (’You can get through any American conversation,’ advised Leiter, ’with “Yeah”, “Nope” and “Sure”.’) The English word to be avoided at all costs, added Leiter, was ’Ectually’. Bond had said that this word was not part of his vocabulary.”

| |||